Don’t forget Microsoft

Understanding the behemoth in Redmond teaches us valuable lessons in cloud infrastructure, startup strategy, and the future of software.

Despite its scale, Microsoft is one of the most overlooked companies in tech.

It is not a beloved consumer brand like Apple, Facebook, Amazon, or Google.

It was not a venture capital success story: Microsoft was too profitable to raise real VC money, so the founders owned 70% at IPO.

It is the oldest of FAMGA, hidden away in a different state.

But there is a lot more to Microsoft than meets the eye. If it plays its cards right, Microsoft can become the first $10T company. And startup founders would be wise to learn from the behemoth in Redmond.

This piece undertakes a daunting set of tasks: 1) understand what Microsoft is, 2) chart a path for its global domination, and 3) apply learnings from the company to the startup ecosystem.

Part 1: What is Microsoft?

Even to avid Silicon Valley historians, Microsoft is hard to define succinctly. No singular power law product defines Microsoft like Google’s Search, Apple’s iPhone, Amazon’s e-commerce, or Facebook’s social network.

Understanding Microsoft’s hundreds of products is daunting. With historical context, we can learn what Microsoft was, in order to discover what it is today.

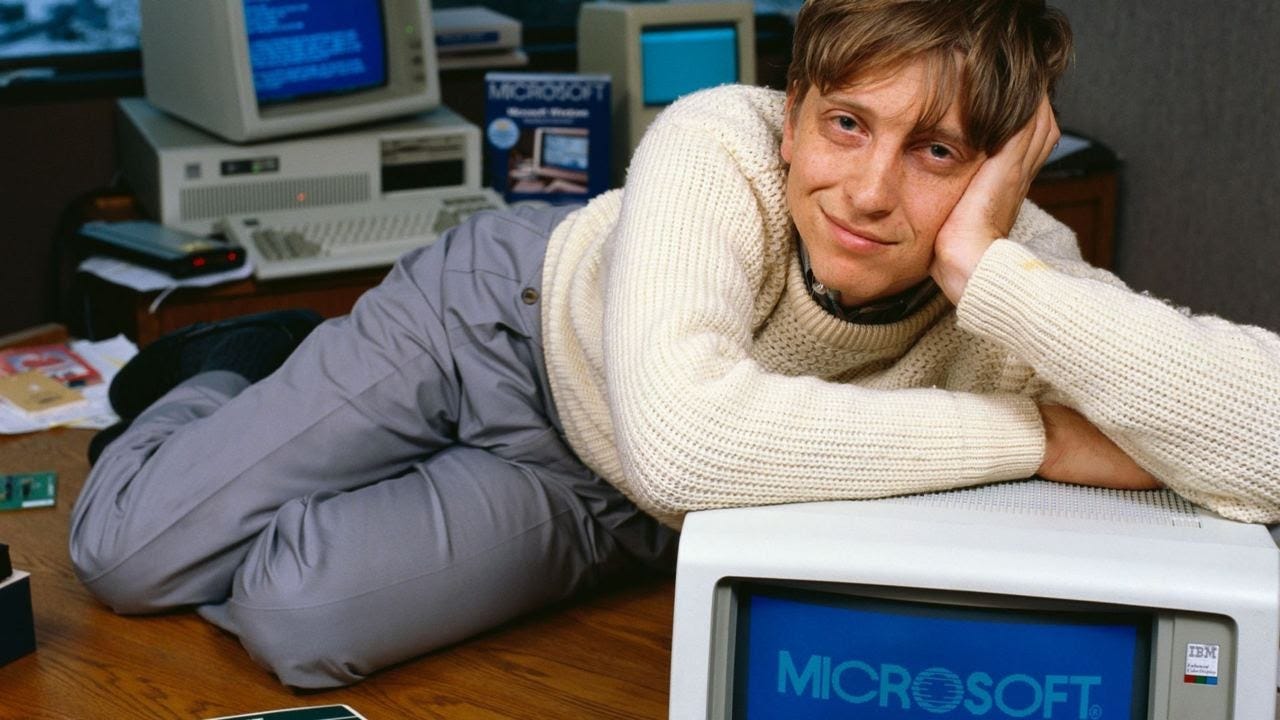

1970s: the founding

In the early 1970s, most people thought personal computers were toys, relegated to hobbyist magazines like Popular Electronics. But Bill Gates and Paul Allen disagreed. As hardware rapidly improved, Gates and Allen realized that the bigger opportunity was not in building the next computer kit, but in building software to make these hobbyist devices accessible to a mass audience.

In 1975, Gates and Allen saw that the Altair 8800 was the first minicomputer with the hardware specs to support a BASIC software complement. They founded Microsoft that year with the founding mission of putting a computer in every home. As Gates described Microsoft: “What’s a microprocessor without it?”

2000s: diversification is for losers

Microsoft rode the PC growth wave for the next 25 years. In 1999, Microsoft was worth $620B, making it the most valuable company in the world. But by 2002, its market cap had dropped 60%. It was stuck in a massive hole dug by the inflated expectations of the dot com boom.

In the 2000s, Bill Gates’ successors took his mission to put a computer in every home too literally, expanding the Windows empire indiscriminately in every direction. Business lines proliferated, and Microsoft’s identity became murky. Was it the Windows company? Office? Xbox? Developer tools? By 2009, the company was worth 30% of its 1999 all-time high.

But diversification was not damning in itself, it was a symptom of a bigger problem: Microsoft’s growth was indexed to the wrong trend.

PC sales were plateauing. Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook were each indexed to mobile or consumer internet – both trends inflected in the late 2000s. Microsoft was indexed to neither.

Without a clear growth driver, Microsoft went on the defensive against the rest of FAMGA in the late 2000s: Bing, Skype, Surface, and Windows Phone were reactive moves.

2010s: finding the next wave

In hindsight, Microsoft’s defensive moves in consumer internet did not align with its DNA. But Microsoft has deep enterprise distribution and trust, something the other FAMGA members do not. Those advantages positioned Microsoft to capture the next wave: cloud infrastructure. Azure, Microsoft’s new cloud computing operating system, quickly became an offensive move.

Azure started in 2006 as an experimental project under Chief Software Architect Ray Ozzie. Guided by the Windows-everywhere dream, Ozzie pitched Azure as “Windows in the Cloud”, or a cloud computing operating system. But what customers actually wanted was an easy-to-use virtual machine in the cloud that Amazon’s EC2 delivered. By the time Azure became generally available in 2010, it had cobbled together product-market fit.

AWS’ four-year head start gave Azure a second mover advantage: it instantly had the accumulated learnings from AWS, which launched 4 years earlier. But unlike Amazon, Microsoft already had enterprise distribution. Once Microsoft started including Azure credits and consumption in its existing enterprise deals, the business took off.

By the late 2010s, Azure’s edge in enterprise distribution created a powerhouse, moving the needle for the entire company.

Azure reached a $10b run rate by early 2019, just nine years after launch. This is faster than AWS, which became generally available in 2006 and hit a $10b run rate by 2016, and GCP which launched in 2009 and hit $10b revenue in 2020.

Today, Azure is a monster with over $30b in revenue, and several $100m+ TCV deals in the Fortune 100. And while Microsoft doesn’t break out the Azure margins separately, we know it’s an attractive business at scale: AWS has 30% operating margins, driving the majority of Amazon’s net income.

In the 2020s, Azure will power most of the company’s growth. Azure gave Microsoft what it needed: a new wave to ride.

Is Azure the fastest B2B product of all time to reach $10 billion of revenue? Azure puts the fastest growing software companies of the past 25 years to shame:

The extraordinary growth of cloud infra businesses wasn’t tracked closely because 1) the key players weren’t venture backed or even standalone companies, and 2) GCP, AWS, Azure were all highly secretive about their early growth, lumping it into “other” revenue buckets to sandbag the breathtaking growth of the segment. The breathtaking cloud computing growth story has only become widely understood in the past couple of years.

Despite AWS brand dominance in cloud computing, Azure is a real threat. While AWS remains the market leader, it has maintained a flat ⅓ of cloud market share, whereas Microsoft doubled since 2017 and is growing faster than both AWS and GCP.

The fact that Microsoft was a PC company and Amazon was a web retailer shows that it almost didn't matter where you started. It matters that you rode the growth wave of the cloud. Microsoft may have too many internal competing interests to recognize that it has become the Azure company, but it should be clear by the late 2020s.

Satya vs. Gates

The MBA case study narrative gives Satya Nadella credit for reinventing Microsoft via Azure, particularly after the lackluster years under Steve Ballmer.

A better framework to understand Microsoft’s leadership is the Roman Empire. Naturally, Gates is Romulus. Nadella is closer to Augustus: undoubtedly a great emperor, but not a founder. Calling him visionary may be too generous, but at the scale of the Roman Empire circa 27 BC, marginal differences in emperorship could have huge impact on civilizational outcomes.

Undoubtedly, Nadella has been an exceptional CEO. He is highly attuned to culture: his superpower was transforming Microsoft from a culture of “no” into a culture of “yes”. By unblocking execs across divisions, Microsoft reaccelerated by the late 2010s, from single digit revenue growth rates to high teens today.

While philanthropist Gates is in favor, business Gates has been out of favor since his notorious antitrust loss in 2000, United States vs. Microsoft Corp, when he got whacked for bundling Internet Explorer with Windows. But let’s not forget the empire he built: by the time he left the company, Microsoft had over $20b in revenue and millions of users.

Nadella inherited an iron man suit which now defines Microsoft: enterprise distribution, user trust, and engineering talent. Azure’s success is the result of a great leader taking advantage of a latent opportunity. Now that we know Microsoft is capable of riding new waves under Nadella, we can explore other latent opportunities to expand the Microsoft empire.

Part 2: The path to $10T

With the right strategy and execution, Microsoft can become the first $10T company.

What would I do if I were running the company? First, I would take stock of its relative strengths: $130B in cash. $2.3T of market cap. Unrivaled distribution in every Fortune 5000 company. 96,000 talented engineers.

Microsoft has powerful intangible assets. Relative to the rest of FAMGA, it may be the only player with some antitrust immunity. This is somewhat structural: software markets are less monopolistic than consumer internet. Even its fastest-growing business line, Azure, only has 19% market share (AWS is at ~30%) – far below any legal definition of monopoly. With nearly unlimited cash and equity, plus some antitrust immunity, Microsoft should be acquisitive.

There is also a financial engineering “growth” strategy that will probably appease shareholders. Tim Cook, for example, started share buybacks in late 2012 after taking over as CEO in 2011, and now consistently buys back ~$20B in shares per quarter. Apple’s share price has grown by more than 10x since Cook took over. It is no surprise that Microsoft started aggressively ramping share buybacks in 2014, the year Nadella took over as CEO.

I would like to think that Microsoft has more compelling growth opportunities than share buybacks, though. We can’t do justice to the entirety of Microsoft’s product suite in 4,000 words, but on the path to $10 trillion, we can explore four new waves Microsoft can ride: demographics, data, developers, and depth.

Demographics expand Microsoft’s TAM

Microsoft’s products are ubiquitous in the Fortune 5000, but conspicuously absent in two growing segments: 1) young users, and 2) growing tech companies. Only 18% of Teams users are below age 35. These are the enterprise customers of the future. Microsoft failed to capture the self-serve motion that unlocked younger demographics and propelled many productivity decacorns in the past five years.

By acquiring companies with complementary demographics, Microsoft can recapture these segments. There is an entire swath of Office-style products with distribution among young + tech audiences, filling Microsoft’s gaps over the past decade:

Airtable: Airtable is a lightweight CRM + Excel, with some automation on top. Microsoft would not need to acquire Airtable if it built out more Excel integrations and improves the UX, but it is trapped in an innovators’ dilemma and can’t alienate its existing Excel user base. A standalone complementary product has more degrees of freedom to capture the next generation of data entry users.

Notion: To oversimplify Notion to its demographics, it is Office 365 for people below age 35. At a minimum, Office should aspire to the ease of use that Google Docs has (Office 365 for people below age 45), but shooting for the stars may help them to land in the clouds.

Miro: This could represent an entirely new Office suite product line – digital whiteboarding. Every enterprise started digital whiteboarding during COVID, which is likely a permanent fixture in a remote and distributed world.

Acquiring these companies would capture the young productivity tool users that Microsoft needs to make Office successful in the 2020s. Given the distinct user experiences, it may be best to keep the products independent, but offer them as part of the core Office suite. This makes Office compelling to a wider audience, reduces its customer acquisition cost, and expands Microsoft’s addressable market.

Microsoft also needs to invest in demographics from the inside: young ex-startup employees could bolster a bottom-up approach to building products for young audiences. According to LinkedIn, Microsoft makes fewer recent grad hires in EPD compared to Facebook and Google. It also has far fewer young VPs and directors (<10 years of experience) than Facebook and Apple. In other words, there are relatively few young people in charge of things at Microsoft. Empowering the new guard can help its products flourish with Millennials and Gen Z.

Developers should love Azure

Azure is undoubtedly a monster business, but it is not cool among the next generation of developers. Without them, Azure will be stuck with top-down sales. In fact, Microsoft’s unpopularity with developers started in the 1990s: the Halloween documents from 1998 show Microsoft’s antagonism towards Linux and open source, which would haunt them for decades.

Microsoft realized this faux pas, and is making up for lost time: Nadella claimed that “Microsoft ❤️ Linux” in 2015, acquired GitHub in 2018 in a splashy $7.5B acquisition, and Azure has deep Linux support (half of Azure workloads run on Linux).

But owning GitHub doesn’t immediately translate into young developers that love Azure. Microsoft’s task is to gracefully harness its newfound developer love. But you can’t force love, like Google tries to force Meet on its unsuspecting users. Microsoft needs deeper OSS support and developer tooling before pushing users towards Azure.

In other words, Azure needs organic adoption to fully penetrate the enterprise. GitHub has developer credibility, but its primary usage is via its command-line tool, where pushing Azure is unnatural. Owning the developer experience at the IDE or Terminal is the path to cross-sell cloud infrastructure downstream.

Microsoft now has a next-gen IDE play through Codespaces, but IDEs are highly fragmented. Rolling up the long tail of IDEs is attractive – they tend to be weak standalone businesses, but increase developer mindshare and offer an on-ramp to Azure. Acquiring Replit is also worth exploring given its strong positioning among young developers who are still malleable.

Data strengthens Microsoft’s core products

Spreadsheets were the killer app for business computing, and Microsoft Excel ultimately dominated the market. It created a generation of data analysts and financial experts. For decades, Excel was the best-in-class business data store.

But in supporting the median, Microsoft lost the frontier. The modern productivity stack fills the gap of Microsoft Excel’s stalled innovation. Weak UX made room for Airtable and Asana. Weak data primitives made room for modern CRUD-based applications. Weak customization and integrations made room for vertical software companies. Weak collaboration made room for Google Sheets. Weak backend architecture and interoperability made room for the modern data stack. Instead of Excel realizing its platform potential, it remained simply a great application.

Microsoft has many pieces that can theoretically support the modern data analyst – data warehousing through Synapse, data pipelining through Data Factory, visualization through PowerBI. But modern teams don’t choose Microsoft, opting for the modern data stack of Fivetran + dbt + Snowflake. Is there a chance Microsoft can win them over?

Microsoft should pay up for best-in-class companies to make up for lost time in winning the business data race. I’d personally consider an acquisition in each step of ELT: Fivetran as the best-in-class E and L, and dbt as the corresponding T. This kills three birds with one stone: position Microsoft to win data pipelining with a leading product suite, inherit distribution to tens of thousands of the best data teams, and push them towards Azure.

Even within Microsoft’s existing product suite, there are massive opportunities for owning customer data. For one, Microsoft is one of the best-positioned companies to compete with Salesforce. Microsoft’s CRM product Dynamics is a sliver of what it could be. Microsoft has the most strategic asset in all of sales and marketing, LinkedIn, and the technological infrastructure to disrupt Salesforce.

Microsoft has a path to becoming the source of truth for customer data through Azure, which would make it mission-critical to all business software. If Microsoft convinces customers to store their customer data in an Azure warehouse (enriched by LinkedIn’s data) instead of a CRM, then the CRM becomes a simple window through which companies access customer data. Other business applications would then build on top of Azure, not Salesforce. If Microsoft divorces the CRM from the customer data system of record, it commoditizes its complement to beat Salesforce.

Depth is Microsoft’s path to winning new markets

Much of Microsoft’s history suggests that its defensive product lines are less successful: Bing lives in the shadow of Google, Surface lives in the shadow of iPad, Skype lives in the shadow of Zoom.

But these product lines were trying to compensate for Microsoft’s weaknesses in consumer internet, not its strengths in enterprise. When Microsoft leans into its enterprise distribution, even defensively, it wins.

If I were in charge of Microsoft’s product strategy, I’d seriously consider competing with any enterprise software company that reaches $100m in ARR. Given its lofty mission and AI-fueled vision, Microsoft may be too proud to clone simple SaaS products. But Facebook has shown that ruthless practicality in copying new startups’ products is a relatively successful strategy.

Enabling and encouraging entrepreneurship internally to build new product lines is challenging, but if Azure could catch up to AWS when it was already at hundreds of millions in revenue, then Microsoft can do it for other categories too. Each incremental product benefits from Microsoft’s distribution, so double-digit market share in these categories is nearly guaranteed.

At the risk of being unfashionably imperialistic: as the largest software company in the world, Microsoft should have a leading product in every meaningful business software category. It had this in the 1990s (Windows, Office, Access, et al.). In the 2010s, the surface area of business software expanded too quickly for Microsoft to keep up in every category.

Microsoft is playing catch up in most markets, so internal product development alone is not enough – it must be complemented by M&A. A few ideas come to mind:

DocuSign: E-signatures are one of the most obvious secular trends in software, and DocuSign is the clear leader. An acquisition could be particularly accretive given Microsoft’s ability to embed the product across its productivity product line.

Figma: Surprisingly, Microsoft has no answer to Adobe, despite being the largest SaaS company in the world. Figma captures both the demographics and depth opportunities.

Zoom: Microsoft has Teams video calling, but Zoom has network effects and became the standard first among young users. This is an opportunity to win the web conferencing market and acquire a distinct audience from Microsoft’s current customer base.

These are not meant to be comprehensive examples. Microsoft should run a triaging exercise to build, buy, or ignore every company in the Bessemer Cloud Index. Plugging new software companies into the Microsoft distribution engine immediately turbocharges their growth, meaning that it can afford to pay above-market prices for great products. As Microsoft competes in new software markets, it expands its TAM, lowers its cost of sales, and gets a new wave to ride.

Gaming

Gaming doesn’t fit neatly into the strategy, so the path to $10T may not seem fully cohesive. But that is the real lesson: it doesn’t need to be. Microsoft is essentially a holding company. New acquisitions and products don’t need to be accretive holistically, but rather to a subsidiary.

In the gaming context, Blizzard helps build the network effects for Game Pass’ 25 million subscribers, and scale de-risks gaming development as a hits-driven business. Now Microsoft is the largest US gaming company – better for the US to own our gaming future instead of China. Gaming is seemingly distinct from its enterprise advantage, but Microsoft is a conglomerate.

$10T: Microsoft’s to lose

Given its market share for its core product lines is much lower than the rest of big tech, the path to $10T is much more in Microsoft’s hands than for other players. How much can Google really do to grow market share? It already won search. Microsoft has many growth levers to pull.

Becoming the first $10T company will require aggressive M&A and product development across categories, and some pride-swallowing to compete directly in emerging software markets. Microsoft has the capital, talent, and distribution to pull it off.

Growth at this scale is unprecedented, but a wealth of opportunities across its product suite suggests the path to $10T is Microsoft’s to lose.

Part III: Lessons for startups

As the largest tech company in the world, Microsoft may not appear to have lessons applicable to startups. But the re-acceleration of the company in the 2010s and the path to $10T tell us about the power of S-curves, compound products, M&A, and second-mover advantages.

Market over execution

Execution is critical, but riding an S curve is the path to win in tech.

Steve Ballmer gets a lot of flack for Microsoft’s underperformance in the 2010s. Undoubtedly, he wasn’t as exceptional as Gates, and company culture stagnated. But the real challenge was category: PC sales were decelerating, while Microsoft was betting on their growth. Reorienting the company towards the growth of cloud infrastructure and business software (which Ballmer should get some credit for) gave Microsoft life again.

Traditional wisdom tells us that founders are the only determinant of startup success. Great founders are necessary but not sufficient. Great product theses and fast-growing categories are increasingly the true bottleneck.

Be acquisitive

Be acquisitive when you have a lot of cash and equity. Nadella seems to appreciate this given his relatively aggressive M&A track record. The path to $10T will require an acceleration of acquisition pace: even the $68.7B Blizzard acquisition represents a mere 3% of Microsoft’s market cap.

As the surface area of new software markets plateaus, tech will transition towards a consolidation era. Startup M&A will become a core part of growth – think of the rollup eras for oil, telecom, and cable. Late-stage startups that are valuation-rich should be considering M&A much more aggressively.

Compound products win

In the 2010s, unbundling made sense because software adoption outpaced the ability for unified product companies like Microsoft to build software. If that pace is flipped, do we see rebundling?

The classic consideration for VCs is whether incumbents can copy the startup’s technology before the startup copies the incumbents' distribution. For the past 20 years, the answer was almost always no – startups achieved escape velocity across categories, seemingly immune from incumbents’ distribution power.

But don’t let that fool you: there is a real bundling effect in software. See Parker Conrad’s Compound Startup thesis, playing out in real-time via Rippling. Office 365 has its weaknesses but is a truly compound product – Microsoft Teams, for example, outpaced Silicon Valley darling Slack just 3 years after launch.

The power of bundling may not have been obvious in the past 20 years because there was so much surface area – every point solution had a high ceiling before incumbents copied it. But the strength of bundling will become a lot more obvious going forward. Tool fatigue and bias towards simplicity are increasingly powerful forces.

The power of cross-sell

Microsoft already has distribution into every Fortune 1000 IT department. This makes it much easier to sell new products than from a cold start. A myriad product line suggests a lack of focus, yet Microsoft is more profitable than all of FAANG – that is the power of cross-sell.

Marc Benioff already understands this deeply: Salesforce has more revenue today in customer service than in its core sales CRM product, and is now tackling marketing and analytics.

Silicon Valley wisdom says to focus on a single product and market. Ballmer did the opposite and built products across categories. This was the right strategy, but in the wrong decade: cross-sell positions Microsoft uniquely well for the 2020s, when antitrust is more threatening than ever. I would rather command 30% market share across many categories than be regulated to death as a monopoly.

Definitionally, cross-sell benefits incumbents more than startups. But it also informs startup strategy: if you have lower CAC on selling incremental products to your existing customer base, it is advantageous to build a deep product suite before selling horizontally.

First mover advantage is overrated

Azure is a real competitive threat to AWS, despite being four years behind. We’ve seen this in the startup context too: Facebook surpassed Myspace and Friendster, Ramp is now a real threat to Brex, Modern Health is a real threat to Lyra. Second movers short-circuit the learning curve of a new market.

For first movers, the lesson is clear: don’t rest on your laurels. But this should also be encouraging for second movers: there is probably more room for new entrants than you think. Think of the degree of competition in other industries like retail or finance – tech has lots of room for new companies before we reach a saturation point.

Consumption-based pricing is a bet on yourself

Consumption-based pricing is the business model that is most aligned with customers. The opposite is simply a poor customer experience: why pay for something before you receive it, or if you may not use it at all? Unsurprisingly, many of the fastest growing companies have some version of consumption-based pricing: AWS, Azure, GCP, Snowflake, Twilio, Scale.

It may feel less “safe” than pure SaaS because the customers are not guaranteed to renew, but it lowers the barrier to adoption. Consumption-based pricing is the best way to bet on the quality of your own product: it perfectly aligns product, customer success, and sales. If customers are engaging with your product, it is a win-win.

Capital: a true moat

The tech industry doesn’t talk about capital as a moat, probably because it benefits those that have already made it. But Azure proves that it works: it spent billions to achieve economies of scale, but the prize is a comparably massive profit center.

In recent startup history, massive capital scale often has failed to change the trajectory of companies: think of the SoftBank mega-rounds that went sideways. Even in the case of Uber, a relatively good company with economies of scale, capital hardly helped: the equity has been roughly flat for the past seven years.

Few companies have the competence to ingest truly scaled capital. When it works, it can really work. The $535m DoorDash Series C, one of the first Silicon Valley mega-rounds, was an extraordinary case study: it quickly won over 50% market share, and was poised to capture the food delivery market expansion during COVID.

Megaproject success can be hard to see when it happens within large companies. Azure and AWS are two of the most successful megaprojects of this century, but were hidden from the public for years, nested inside much larger corporations. Starlink, the global satellite internet network, is only possible given the scale of SpaceX’s core launch business, but could be one of the most successful megaprojects of our time.

Conclusion

As a student of Microsoft, 4,000 words is woefully insufficient to fully digest its complexity. Everyone in tech should spend their own time trying to learn from the greats, and Microsoft deserves special attention.

So what is Microsoft? It was the Windows company in the 2000s, became the Office company in the 2010s, and is becoming the cloud company in the 2020s. It is the sum of its core advantages: enterprise distribution, user trust, and an engineering talent vortex.

With these advantages on its side, my money is on Microsoft as the first $10T company. Azure alone has a path to hundreds of billions in revenue, and would be one of the largest standalone companies in the world today. Getting to $1T in revenue will require ruthless expansion across product and M&A in every software market.

And in the startup context, Microsoft is a treasure trove of lessons: it teaches us the power of distribution, product bundling, M&A, and compound growth.

Thank you to Brandon Camhi, Pranav Singhvi, Sam Wolfe, Harry Elliott, Everett Randle, Melisa Tokmak, James McGillicuddy, and Tomcat Sanderson for their thoughts and feedback on this article.

Excellent analysis

I've recently read a similar article but for Apple. It said that Apple is going to be a $10T company and this article insists on the same. Interested in keeping watching these companies.

https://glasp.co/#/kei/?p=FARmiDEnYAvVw4aEEoi8